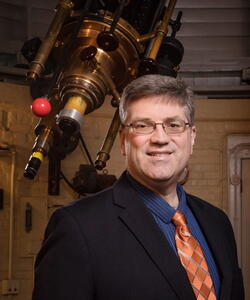

As one might expect on a bitterly cold Thursday evening, the bar fills up early. Conversations overlap, beer is served, glasses clink. Then things get interesting. Someone sets up a projector. As the crowd jockeys for a good view, in walks Charles Gammie, an Illinois astronomy and physics professor who was part of the effort that produced the first-ever image of a black hole. He’s here to talk about something much closer to home: the Moon, what we know, how we know it, and what we still don’t.

Questions fly easily. How much of a rocket’s mass is fuel? Why is the lunar south pole such an ideal landing site? Why go back to the Moon at all? Laughter and jokes punctuate the discussion, and no one seems intimidated by the expertise on display.

This is Astronomy on Tap, a monthly public lecture series hosted by the Department of Astronomy that, for the past 10 years, has brought cutting-edge science out of the classroom and into the community—one informal, conversation-driven evening at a time. Part of a national program with chapters in cities and universities around the world, the Illinois series returns month after month to 25 O’Clock Brewing on the third Thursday of the month.

Where it began

Astronomy on Tap began with a simple idea: make scientists feel approachable to the public, or, as founder and director professor Joaquin Vieira puts it, make scientists feel like “real people.”

“The original goal was simply to allow the public to interact with real scientists conducting cutting-edge research,” said professor Joaquin Vieira, who founded the program and still serves as its director. “Growing up, I didn't have access to that. I was first gen. I didn't know any scientists. I was into science, but I didn't know any scientists or anything like that. They weren’t real people. It was like Carl Sagan you saw on TV.”

The bar setting was a deliberate choice. While students regularly encounter faculty through classes and campus events, Vieira saw something different in moving the conversation off campus.

“Bars have been used as informal places of congregation and discussion for thousands of years,” he said. “Even though you don't necessarily need to go there to drink or partake, it is kind of a natural place to gather in an informal setting.”

That informality proved essential from the very beginning.

“The first Astronomy On Tap was packed,” Vieira recalled. “I remember it being a smallish room, us worrying, would anybody show up? And instead, people were out the door.”

For longtime attendee and Champaign resident Dave Leake, the concept itself was initially surprising.

“To be honest, I don’t recall my first AOT,” he said. “But I do remember wondering if it was a real event. I mean, an astronomy talk in a brewery? What a concept!”

What keeps people coming back is simple.

“People can ask questions at any time, and you’re guaranteed to learn something new,” Leake said. “I think it’s a wonderful thing that the astronomy department offers as outreach.”

A different kind of talk

Astronomy On Tap is intentionally unlike a traditional academic seminar. Rather than long slide decks dense with high concepts, speakers are encouraged to keep things loose and let the audience guide the discussion.

“A lot of academics, if we conceive of giving a talk, we usually slip into the default, which is to talk about our super-specific research and to use jargon,” Vieira said. “We really want Astronomy on Tap to be a dialogue, not a speaker-led seminar where the speaker just conveys expertise to the audience.”

Preparation, paradoxically, is kept light. That format benefits not only the audience but the scientists themselves.

“You really learn to break it down into concepts,” Vieira said. “That skill has been important in my later life when I talk to administrators or people in government, because you can break it down in a way that a non-expert can understand why it's important and cool.”

A community within the department

While Astronomy On Tap is outward-facing by design, its impact within the department has been just as significant, especially for graduate students and postdocs who help organize and run the series.

Graduate student Spencer Wilken first encountered Astronomy on Tap as an undergraduate.

“I attended AOT when I was an undergrad,” she said. “When I came back, it just felt so obvious because I love the outreach, and it is a critical outreach for our department.”

For postdocs like Arran Gross, the program offered something less obvious but just as important: connection. Even attending the event has given those within the department a chance to interact with others that they haven't had before.

“To me, it really helped me feel like part of the department and that there was a community within it,” Gross added. “Before, it was a lot of going to work every day and sitting in my office by myself. This was a nice introduction to a big swath of people in the department.”

That sense of belonging is something organizers consistently return to.

“As I'm deciding what it means to be an astronomer, I get to see others do it and connect with people outside our department,” reflected Wilken.

Learning goes both ways

Astronomy On Tap’s emphasis on accessibility doesn’t dilute the science. Faculty members frequently note that the experience reshapes how they think about communication.

“When you interact with people in a setting like this, you start to get an idea of which parts of your story are comprehensible and which parts are incomprehensible,” said Gammie. “And that's super valuable.”

Gammie also emphasized responsibility.

“Science is really no good unless you tell people about what you're doing,” he said. “At a public university, the public supports our work, not just in teaching, but also in research. So, I think it's super important to pay back as much as we can.”

Even seasoned experts find themselves learning.

“I learn things in these talks, and I get to ask the questions too,” Vieira said. “Like, ‘Wait, why does that work? Or can you explain that differently?’”

Memorable moments

Graduate student and organizer David Vizgan recalled attending his first Astronomy On Tap shortly after arriving on campus.

“Professor Gammie gave the very first AOT that I saw,” Vizgan said. “It was about the Event Horizon Telescope and making images of a black hole. It completely blew my mind. It was a better explanation than probably any press release or paper could.”

Each year, Astronomy On Tap also participates in the Pygmalion Festival, blending science and the arts to create memorable talks for its founders and organizers alike.

Gross pointed to one especially powerful Pygmalion talk from a couple of years ago.

“We ended that one with this groovy new-agey musical act, with Joaquin doing voice-overs,” he said. “It was a very existential piece of art. Having somebody make such a really emotional plea—that what we do as scientists is connected to the rest of the world—was incredibly impactful.”

Why it matters

At its core, Astronomy On Tap is about bringing science to the community.

“You have to meet people where they are,” Vieira said. “Otherwise, what's the point?”

That philosophy feels especially urgent now.

“I realized, when I started teaching, just how poor science literacy was,” Vieira said. “That’s concerning because half the economy is driven by science and technology, but if you don't tell people, show them, and let them engage with it, they won't support it.”

For organizers, the mission is both professional and personal.

“If we can go out and spread a little joy, a little science, and a little space, then that's a win,” Wilken said. “That’s a win for our department, our campus, and our community.”

On any given night, as questions echo through the bar and conversations linger long after the final slide, it’s clear why Astronomy On Tap has endured. It’s science as conversation—welcoming, human, and shared—and 10 years in, the room is still full.